School of Education

Education shortcuts: worthwhile or worthless?

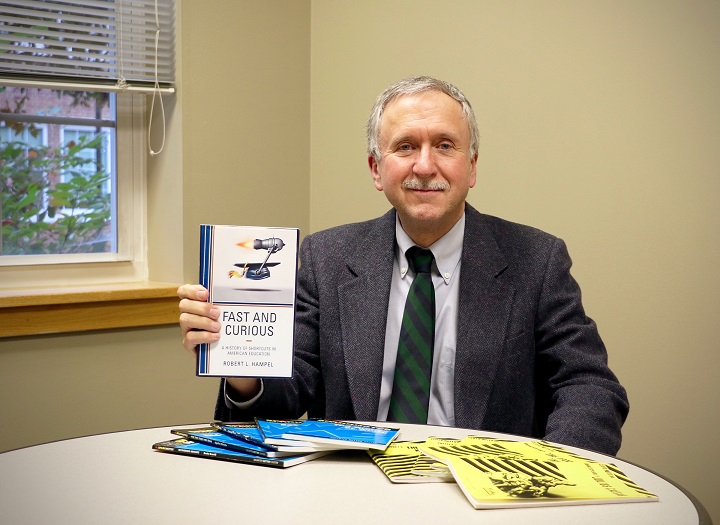

School of Education professor Robert Hampel publishes book on A History of Shortcuts in American Education

“A Fascinating Money-Making Art Career Can Be Yours!” Norman Rockwell promised aspiring artists in an ad for his Famous Artists School, where 24 home study lessons could turn their talent into cash.

Or, high school juniors–pained by Twain or mystified by Melville–could spend a dollar for a little yellow Cliff Notes version to decipher the novel they were expected to read.

Shortcuts.

That’s the subject of University of Delaware professor Robert Hampel’s new book, Fast and Curious: A History of Shortcuts in American Education (Rowman and Littlefield, 2017).

The book begins with Norman Rockwell’s correspondence school and ends with Evelyn Wood’s speed reading classes. Along the way Hampel looks at Classic Comics, Paint by Numbers, shorthand, Cliff Notes, phonetic spelling, Teach for America, three-year bachelor’s degrees, law school at the YMCA, and other streamlined paths to education.

“I began the book when a friend predicted that legal drugs that would soon wipe out his field of educational psychology. He claimed that everyone would become more focused and motivated with the right pills,” said Hampel, professor in the School of Education and education historian. This conversation inspired him to examine the many ways Americans have tried to make education less onerous.

These shortcuts fall into two categories. He calls one cluster the “faster and easier” options, supposedly saving students both time and effort. Experts would reveal the tricks of the trade in short simple lessons.

The precursor of what we now call distance education—correspondence schools—was the most popular faster/easier shortcut. More people enrolled before the Great Depression than started college. Arthur Murray dance studios began as home study lessons; so did Charles Atlas’ bodybuilding course. The largest school in the world wasn’t Harvard or Yale; it was the Famous Artists and Famous Writers schools, enrolling over 150,000 students by the mid-1960s, including a blonde cheerleader who Rockwell had sketched in 1938.

A second cluster of shortcuts are the “faster and harder” options. In exchange for a burst of strenuous effort now, students would save time and effort later: that was the offer extended by many universities.

Unlike the faster/easier options, many of the faster/harder pathways were entirely legitimate, free of hyperbolic and deceptive claims. Given the right amount of effort, you could finish Harvard in three years, get an M.D. degree six years or become a teacher without majoring in education.

Students who wanted to save time could find the express lanes, but the eager few saw that the majority of their classmates had no interest in picking up the pace. For instance, more than half of Harvard freshmen today could finish in three years or earn a master’s in four; approximately 3% do.

Do shortcuts work?

The obvious question is, are there any legitimate shortcuts to learning? To which Hampel responds, “It depends.”

Faster/harder shortcuts can be beneficial, if time and/or money is your limited resource. But they typically require enormous focus that minimizes the opportunity for people to explore, make mistakes, or change direction. Students who accelerate through college may sacrifice sports, clubs and social activities that could otherwise enrich their academic experience.

Meanwhile, faster/easier shortcuts are often downright risky.

“Beware of anyone who tells you that education can be effortless,” advised Hampel. “Shortcut advocates often make extravagant claims. As they arouse hope, they encourage unrealistic dreams. The lesson most people need to learn is to be wary of inflated appeals designed to get their money.”

Hampel asserts that the best shortcut is to formulate a strategy. He recommends approaching education as you would undertake serious pursuit of a sport—committing to deliberate practice. “If you want to succeed in golf, you don’t just hit balls at a driving range. You get advice from a coach, work on particular shots, learn from mistakes, and persevere. Otherwise the pursuit of knowledge (or golf) may prove aimless and frustrating.”

Fast and Curious: A History of Shortcuts tn American Education is available through Rowman and Littlefield on November 30, 2017.

Article by | Photo by Liz Adams